Correctness Is Upstream of Everything

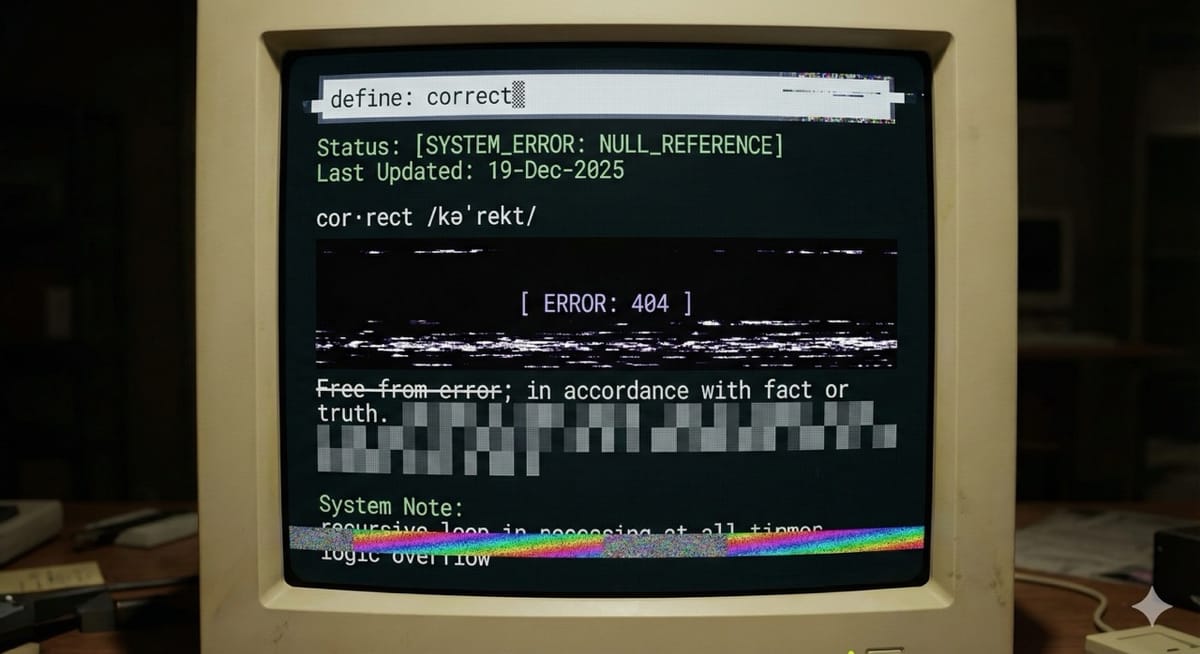

Most AI projects don't fail because the model is dumb. They fail because nobody can answer a brutally simple question: what would correct even mean here?

Microsoft has spent billions on Copilot. They've bundled it aggressively into enterprise packages. And yet, the adoption numbers are… not great. People try it once or twice, get weird results, and quietly stop using it.

The instinct is to blame the technology. The model hallucinates. The AI is unreliable. We need better models.

But that's not what's happening. What's happening is something much more human, and much more fixable—if we're willing to be honest about it.

If you can't define correctness, you can't measure it. If you can't measure it, you can't improve it. Everything downstream—the architecture decisions, the context engineering, the model choice—becomes an elaborate castle built on sand.

And here's the awkward part: we don't just lack a definition. We often change our definition mid-stream, then blame the system for being unreliable.

Why We Stay Vague

Humans have been optimizing for social cohesion for about half a million years. We're really good at it. We use vagueness as a social lubricant—it keeps options open, avoids conflict, lets everyone nod in a meeting and disagree later in production.

I call these "fluffy words." Words like "actually" or "a lot" or anything that wasn't a specific number with a specific claim. You'd use them because you wanted to go along and get along.

This has worked for us as a species. It does not work with AI systems.

When you leave things conveniently vague with an AI system, the system will decide for you. And the outcome looks like unreliability. It looks like poor quality. It looks like the board asking, "Where is our AI product? Why is it bad?"

Most of the time, that's just human undecidability reflected back at you.

Probabilistic Systems Are Different

In traditional software, we pretend "correct" is obvious. The program passes the tests or it doesn't. It's binary. You have functional requirements, and the software either meets them or goes back to QA.

AI doesn't work that way. Correct is rarely binary. It's actually a bundle of competing requirements that we often don't honestly debate upfront:

- How truthful does it need to be?

- How complete?

- What tone should it use?

- Does it need to comply with specific policies?

- How fast does it need to respond?

- When should it refuse to answer?

- Does every response need an audit trail?

These requirements often compete with each other. Do you want the system to answer quickly and confidently? Or do you need it to match finance numbers exactly, even if that takes longer? That's not an easy choice, and it's definitely not a choice the model should be making for you.

The Moving Goalpost Trap

Here's a pattern I've seen over and over again:

Week one: "Correct means the answer just has to sound plausible and save time."

Week three: "Actually, correct means it matches the finance numbers exactly."

That's not a small change. That's a fundamental redefinition of the system. And when you discover correctness over the course of a build, you're going to discover lots and lots of architecture changes. Your engineers and AI architects won't know what you really want—they'll just go back and forth because the target keeps moving.

I've seen teams argue in circles for weeks because one stakeholder implicitly believes "correct" means bold and confident, while another believes it means precise and cautious. Neither wrote it down. Neither debated it upfront. They just kept blaming the system.

When Metrics Become Targets

Once you admit that correctness is upstream of everything, you hit the next landmine: measurement distorts behavior.

Goodhart's Law gets quoted because it's annoyingly true: when a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure. In AI, this becomes: if you pick a proxy metric for correctness, the system will learn to win the proxy—even if that proxy is different from what you actually care about.

This is why hallucinations persist. OpenAI has published research showing that common evaluation setups reward confident answers over honest uncertainty. If you never defined correctness, and your system rewards guessing, then systems learn to guess.

Think about it: how often do we tell models in system prompts that they "must give an answer"? We're inadvertently training them that uncertainty is unacceptable—that they should answer even when they don't know. Then we blame the model for hallucinating.

This isn't really a model problem. This is an us problem.

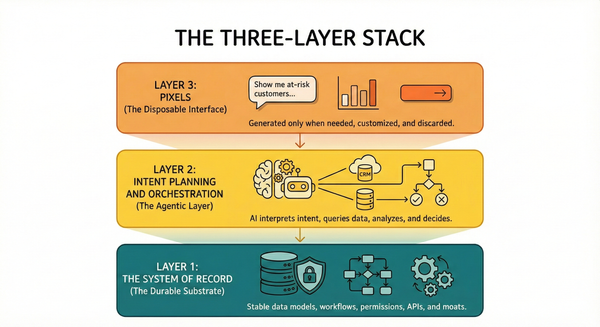

A Framework for Thinking About Correctness

So how do you actually define correctness in a way that's useful?

Think of it as three things:

1. The claims your system is allowed to make. What can it declare? Inventory levels? Customer call counts? Sales forecasts? Get specific.

2. The evidence required for each claim. Where does the system get its information? How do you trace provenance? What sources are authoritative?

3. The penalties for being wrong versus staying silent. This is crucial. Is it acceptable for the system to say "I don't know"? What's worse—a wrong answer or no answer? In a board deck, a single digit off destroys trust. In a customer chat, a cautious non-answer might be worse than a reasonable guess.

If you can't define correctness in these terms, you haven't broken down the problem enough. You've left it at a human level where it's conveniently vague.

This is also why good evals aren't busywork. Writing evaluations forces you to think through what correctness actually looks like. It surfaces disagreements before they become architecture problems.

Why This Matters For Your Next Prompt

I've spent most of this piece talking about systems and enterprise AI because that's where the stakes are highest and the failures most visible. But this insight is fractal—it applies at every scale.

When people watch me prompt, one thing they notice is that I always give the model a clear sense of what an expected output should be. Even on a short prompt. What does good look like? What format? What level of detail? What should it do when uncertain?

Prompting is kicking off a workflow. Prompting is telling a model what good looks like. Every prompt implicitly imposes a quality bar—either one you've chosen deliberately, or one the model invents for you.

So here's my challenge to you: the next time you prompt a model, or design a system, or sit in a meeting about AI adoption—ask yourself:

Do I actually know what good looks like?

If the answer is no, that's not the model's problem to solve. That's yours.

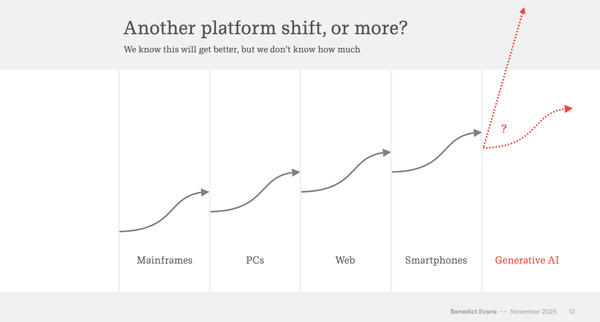

And honestly? Figuring it out is some of the most valuable work you can do in the age of AI. The models will keep getting better. The humans who can define correctness clearly—who can translate vague business requirements into specific quality criteria—those are the ones who'll actually get value out of all this technology.

The good news is, you can start right now. You can start with your next prompt.